A photo project about India’s involvement in the Korean War

A photo project about India’s involvement in the Korean War

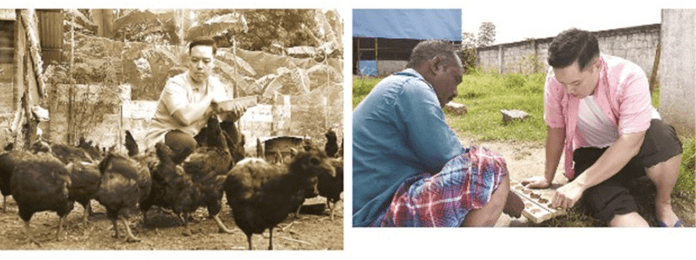

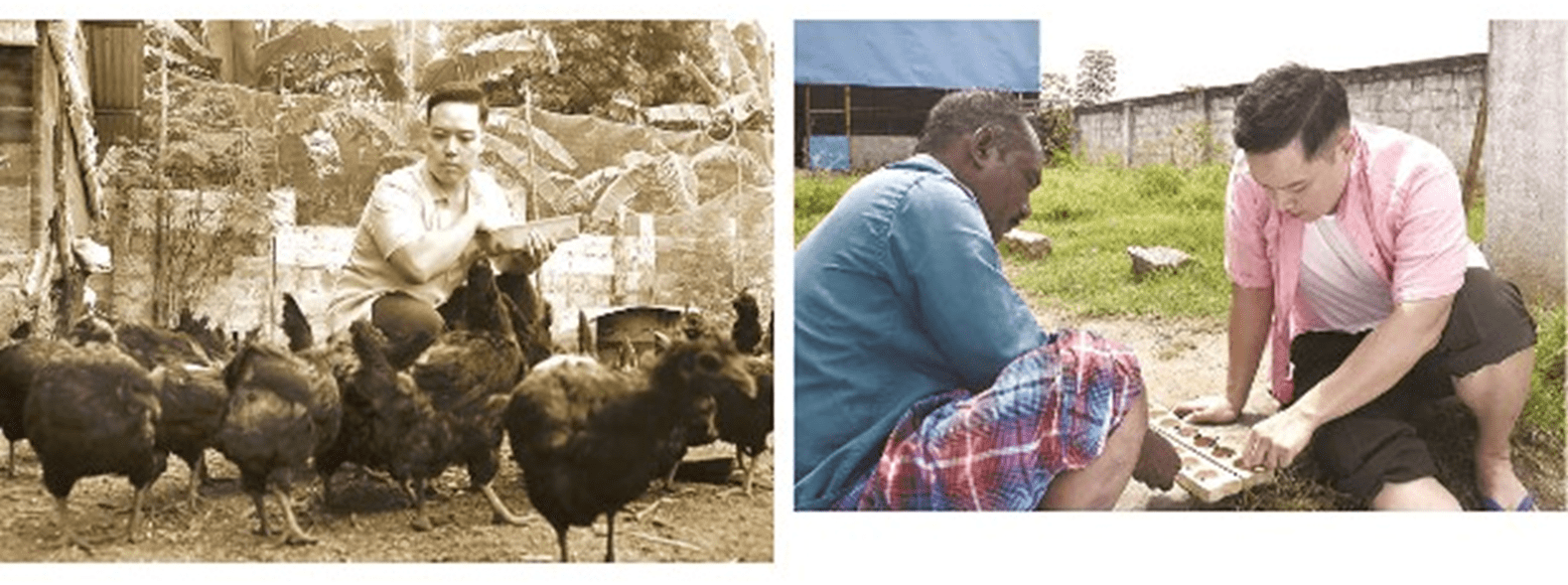

The project highlights the effects and consequences of the 1950 Korean War and India’s involvement in the aftermath. “Chicken Run is a digital photo-fictive archive that Parvathi and I have created for the Chennai Photo Biennale 3 Maps of Disquiet. The project uses archival and fresh photography, archival videos, drawings and creative writing to look at the life of a Korean POW (prisoner of war), the elusive Mr H who winds up in Chennai at the end of the Korean War in 1954. A little-known fact about this war is that 6,000 Indian soldiers travelled to Korea as part of the Custodian Force of India (CFI) in 1953. They were authorised by the United Nations to guard and protect thousands of POWs who were not willing to repatriate to their home countries. In the end, some 80 POWs chose to come to a neutral nation, India. Some stayed on and found occupations such as chicken farming others tried to go on to western nations from here. Our project took that piece of history and expanded on it,” says Nayantara Nayar.

Parvathi’s father was a General in the army who loved art, poetry and photography. He died when Parvathi was young and left all his papers to her. “The origins of Chicken Run are autobiographical. I thought it would be meaningful to do a creative project inspired by these personal archives with Nayantara. And so the project Limits of Change was born almost four years ago which was later supported by InKo Centre. Chicken Run is a fictional combination of art and storytelling, based on historical research, about this almost forgotten but important part of Indo-Korean history,” shares Parvathi.

All the video material used in the photo project was shot by Parvathi’s father in 1953/54 in the demilitarised zone in Korea and Chennai. “For other archival photographs, we had to do a lot of digging. I remember us spending many months just trying to track down photographs, archives, and permissions, sending off dozens and dozens of letters. We were fortunate to get positive responses, guidance and permission from many archival sources and photographic collections such as the Pepperdine Library, and the Peabody Library (Harvard). I also took fresh photographs that fill in many of the Chennai gaps of our story of Mr H,” she remarks.

Explaining the research process, Nayantara adds, “We needed books, articles, videos, essays- anything that gave us more details on India’s role. The Korean War is well documented in the west, but not a lot has been written about it in our country. Our first leads were from General Ian Cardoza who got me access to the United Services Institute library in Delhi. I also had a chance to interview a CFI soldier, General Mathew Thomas. We talked to Jairam Ramesh, who gave us some invaluable connections and led us to the Nehru Library in New Delhi. One of the biggest resources was a book by General Thimayya who was Chairman of the Neutral Nations Repatriation Committee in 1953 – this was a committee set up along with the CFI by the United Nations to oversee the POW process. My aunt tracked it down through the Thimayya trust. Later, they also put us in touch with a scholar from Korea, Professor Ra who had translated Gen Thimayya’s book into Korean; he shared some useful perspectives from the Korean angle, as well as some maps he had come across, showing the Indian setup in the DMZ.

A photo project about India’s involvement in the Korean War

A photo project about India’s involvement in the Korean War